GIANTHROPOLOGY.ca

GIANTHROPOLOGY.com

Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey

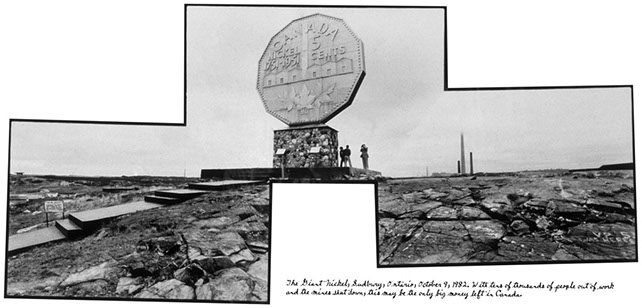

The Giant Nickel, Sudbury, Ontario, October 9, 1982. With two million people out of work and the mines shut down, this may be the only big money left in Canada.

THE PANCANADIENNE GIANTHROPOLOGICAL SURVEY

1981 - 1990

This overly ambitious photography project sought to investigate the true meaning of Canada through the science of Gianthropology. Over the period of exactly one decade Henri Robideau's photographic experiences took him through triumph and tragedy as he explored the land of his ancestors, digging into its history while on the lookout for its Giant Things.

Giant Igloo Church and view down MacKenzie Road, the very heart of beautiful downtown Inuvik, N.W.T., August 11, 1981.

Giant Spot in Canadian History, Craigellachie, BC, October 1, 1982. It was here that two bands of steel were joined binding Canada into one physical country from Ocean to Ocean. Some historians believe Canada was truly born in the month of November 1885, with the completion of the transcontinental railroad on the 7th of that month and the hanging of Louis Riel two weeks later in Regina, Saskatchewan.

Giant Pysanka (Ukrainian Easter egg) Vegreville, Alberta, August 26, 1983. Designed and built by Ron Resch in 1974-76 to commemorate the Mounties 100th anniversary. This 10 meter high aluminum egg was laid with the aid of a computer.

Giant Shaft, middle of nowhere (closest town Grand Falls) Newfoundland. When the Federal Government tried to find the appropriate gift for Newfoundlanders to commemorate the completion of the Trans Canada Highway, they decided to give them the shaft. August 2, 1984.

Haida singers outside the British Columbia Supreme Court celebrate the handing down of suspended sentences in an anti-logging case which saw their people charged with trespassing on their own land. The Haida have never agreed to relinquish their territory and are engaged in a continuing land claims dispute with federal and provincial governments. On the left their leader Miles Richardson gets swarmed by the media while on the right artist Robert Davidson, with drum in hand, directs the song. Vancouver, British Columbia, December 6, 1985.

Giant Chop Suey Bowl, corner of Pender and Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Chinese New Year, February 9, 1986.

French tenements on Mechanic Street, French Hill, Leominster, Massachusetts, October 10, 1987.

Colombe de la Paix Géant. The theme of Montreal's October 20, 1988, peace march- "War Is Not A Game" - was aimed at the city's school children and concentrated on the role war toys play in preparing them to accept war and violence as only a game. Children all over the city "surrendered" their war toys for a display on one of the parade floats.

Giant Luminous Cross ski hill, mont Bellevue, Sherbrooke, Quebec, March 25, 1989. The Cross was erected in 1950 to commemorate the Year Of Peace declared by Pope Pius X11.

PORTAGING THROUGH HISTORY

1980 marked the beginning of my second decade in Canada. This was a time of great change for me, for Canada and for photography. My work up to this point had both American and Canadian elements, the Giant Things series even included more American than Canadian examples. My research on the life and photography of Mattie Gunterman likewise spanned the border as she too had been an American immigrant to Canada. Now, wanting to turn solely to Canada for my photographic inspiration, for a better understanding of the place where I was living, and for reconnecting to the land and history of my ancestors, I invented the Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey.

In 1980 Canada was on a course of redefining itself and determining its own future. The era of “Vive le Québec Libre!” had come to a humiliating conclusion for Rene Levesque’s sovereignty referendum defeat on May 20, 1980, signaling the county would not be broken apart by a Quebec departure. Following this, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau aggressively set in motion the gears of constitutional repatriation and Canada was about to sever its colonial ties from England. Out would go the British North America Act and the Indian Act, England’s colonial structures upon which Canada had operated since its inception in the mid 19th century. In would come a new, diverse yet unified post-colonial nation under its own constitution. Or maybe something like that? And what about the First Nations? Where would their power, self determination and sovereignty over their unceded land fit into the grand new scheme? The Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey would be there studying the big changes unfolding across Canada.

Photography in 1980 was reaching the apex of its climb to the top of the Art World. Through all of its manifestations from its birth in 1839, the medium constantly fought a back and forth battle as to whether it really qualified as ART. Now at the end of the century, the end of the millennium, it was indisputably THE ART. Every gallery was showing photography. Every critic was writing about photography. Every art school, everywhere, had opened a photography department. Photography’s existence as a journalistic and documentary medium was being transformed by the rise of conceptually and intellectually inspired camera imagery which lifted its contemporary artist practitioners to that exalted place once occupied by the likes of Michelangelo. In a world where photography replaced painting, size became a significant factor, and an 8 by 10 inch perfectly executed photographic print could no longer be the match for one the magnitude of a masterpiece hanging in the Louvre. A photograph had to be as big as a Wall. This was a good time for the Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey photography project to come along. I made panoramas bigger than anything I had yet produced, ranging from five to ten feet wide, and included my hand written anthropological data and anecdotal narrative account of the true meaning of Canada.

And so, with these considerations in mind, I devised the course my photography would take over the next decade, starting January 1, 1981 and ending at midnight December 31, 1990, precisely ten years. The ambitious Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey would investigate the true meaning of Canada, size up the bigness of Canadian humanity, and chronicle its progress along the path of a supposedly post-colonial destiny. I would cover this vast country, the second largest in the world, by going out on ‘Digs,’ searching for Giant Things, Big Events, Giant Crowds, Giant History, anything Hyperbolically Canadian. I would visit the lands of my ancestors and like the voyageurs amongst them, portage the whole country – but instead of coming back with furs, I would come back with panoramic photographs. When it was all done, I’d turn it into a book.

I wanted to make the first Dig a significantly Canadian experience, choosing the Arctic as my destination. It would have to be a summer experience and I would take my whole family along. I called it The North Pole Dig. It was an opportune time for driving to the North Pole as the Dempster Highway had just been completed and one could travel by road all the way to Inuvik. After that first Dig, others followed on an approximately yearly basis, lasting from a few days to a few weeks. I always came home from the Digs with enough photography to spend the winter in the darkroom processing my film, making proofs and printing exhibition panoramas.

In January 1983, I had my first exhibition of the project, the inaugural show at the new Coburg Gallery in Vancouver. In 1984 I self published The Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey Set Of 18 Postcards based on images from my 1981, 1982, and 1983 Digs. Also in 1984, thanks to the Canada Council, I conducted the Big Dig, photographing and videoing the whole country from Victoria, BC, to St John’s, Newfoundland (and back). By the mid 1980’s I had made about 50 framed large scale panoramas and I was booking exhibitions of the Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey across the country. By the late 1980’s the locations depicted in my panoramas seemed too heavily weighted toward western Canada, so in the spring of 1987, I was enticed to eastern Canada by a fortuitous teaching position at Concordia University in Montreal and the offer of a book deal with publisher Summerhill Press in Toronto. Since my self allotted decade of Pancanadienne Gianthropology was nearing an end, I figured I better finish it off in eastern Canada. I talked my family into moving east. We packed up our entire household into a ten ton truck and drove to Montreal.

On July 14, 1987, our second day in Montreal, a massive storm hit the city. It rained eleven inches in one hour. The Décarie Expressway was seventeen feet under water. Two people drown in their cars. 60 of my panoramic exhibition prints made between 1981 and 1987 were destroyed in the flood. My wife lost 30 years worth of her works on paper. Artist Sorel Cohen generously offered us her studio for a recovery operation and we spent our first month in Montreal unframing, drying and salvaging as much of our work as we could, but in the end the loss was substantial. I packed up my flood damaged work into a couple of crates and moved on. My teaching position at Concordia started in the fall semester, helping take my mind off the summer’s disaster until I came home one evening to find our apartment broken into and my Leica gear stolen.

Then I got a call from Gordon Mantador of Summerhill Press and the way my luck was going I thought he might cancel the book offer, but he consoled me by simplifying the plan and saving a semblance of the Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey. In 1988 Pacific To Atlantic Canada’s Gigantic! came out featuring single frame Giant Things images and not my captioned panoramas but instead the text authored by Peter Day who was instrumental in advancing the project. This little volume wound up being the definitive documentation of the project’s Giant Things up through 1987 and the only book to come out of the Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey.

We lived in Montreal for about four years and during that time I undertook a number of Digs around eastern Canada and the Maritimes and since this was the cradle of my gene pool I spent a good portion of my time investigating my roots in Quebec, New York State and New England. I began printing again, but differently. I stopped making expensive framed panoramas like those destroyed in the flood. I printed on resin coated paper that could be staple gunned to the wall and rolled up and sent inexpensively in a tube for an exhibition. Working with resin coated paper also lead me into designing long narrative scrolls laid out on rolls of butcher paper. This became a new way for me to hammer out a story and edit the photos to go with it. The final work would then be made into narrative panels with a selection of montaged photographs.

In its final year, 1990, the Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey swung into a fever pitch of photography, fueled by a Canada Council grant that sent me and my camera to Europe, visiting Amsterdam, Spain, France and Ireland. When I got back to Montreal, Indigenous issues were coming to a boil across Canada – first with the rejection of the Meech Lake Accord by Elijah Harper’s “No” in the Manitoba legislature and then the armed invasion of Kanehsatake by the Sûreté du Québec in an attempt to seize Kanien’kéha:ka land for an Oka town golf course expansion. After photographing at Oka, I ventured to Japan in the autumn for one month, then landed back in Vancouver till December as the assistant to Green Peace photographer Robert Keziere, finally returning to Montreal for the winter holidays and the December 31, 1990, self imposed deadline for the end of the decade of the Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey.

We moved back to Vancouver, back to the unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsliel-Waututh First Nations, in the spring of 1991.

After spending a decade of collecting images, data, historical research and Canadian experiences, it was time to come to some conclusions and put forward my photographic narrative. Over the ten years, I had exposed hundreds of rolls of 35mm, 120 film and sheets of 4x5, something on the order of 20,000 exposures from which about 1500 panoramas could be produced. The job of proofing the 1500 panoramas needed to be done before a real edit of the overall project could be considered for making a book. This took me till 2002. The book has had many fits and starts since then – the latest in 2018 – but it has not, and perhaps never will be produced in my lifetime.

The best thing to come out of the decade of Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey photography was the first thing I produced once I got my darkroom set up and running again – a new piece for the 500th anniversary of Indigenous resistance against colonialism, an eight panorama and sixteen single image narrative titled 500 Fun Years. Addressing the questions about Canada posed at the beginning of the project in 1981, 500 Fun Years examined the history and persistence of colonialism with documentation of current events highlighting the struggles of Indigenous Peoples to protect their lands and cultures from the capitalist interests of private property, resource extraction and the genocide of assimilation.

Over the last thirty years, since the end of the Pancanadienne Gianthropological Survey, I have mined its treasure trove of images for inclusion in my narratives, which continue along the documentary, historical and autobiographical lines, and occasionally stray into a quasi fictional abstract zone I call The Ironic Tragedy of Human Existence. And even though I have long since abandoned Gianthropology, I still can’t help myself from photographing a Giant Thing should one pop up around the next corner.

Skookum demonstration in support of the besieged Kanehsatake Mohawks, Oka, Quebec, July 29, 1990. At the microphone is Elijah Harper. Just a few weeks before the attack on Kanesatake Elijah Harper's simple 'No' delivered in the Manitoba Legislature, killed the arrogant Meech Lake Deal which recognized only French and English colonizers as founders of Canada while ignoring the sovereignty and preexistence of the First Nations.

© 2021 Henri Robideau